A neighborhood dies a second death 10 years after Occupy Detroit.

By Margo B and By ANDREW FEDOROV(smartset.com) and featuring Gus Burns | fburns@mlive.com FBurns wrote original aricle at end which brings to full circle this article and update)ALL Contributing writers represented here in thier entirety so this 7 year journey unfolds correctly

It was my old neighborhood. I grew up in Conant Gardens /Grixdale ...collectively lets call it the NorthTown neighborhood.

However in 2015 , after living in NYC during Occupy Wall Street, I return to Detroit. I learn that Grixdale has the rep of being most destroyed eastside neighborhood...Trashed. Burnt... all those wooden brick porched houses- all those 4 squares.(You Tube videos by charlie313bo )

Toast. Were they too big to maintain? I have a theory. The houses were purchased by successive groups of people who were ultimately not interested in being neighbors.

Conant Gardens once Irish , then black. Later in the century more oversea immigrations. Slowly the Grixdale zipcodes are predominately settled by various middle eastern occupants with entrepreneurial spirit or better auto industry jobs...So far so good. Until it was not. Drugs and rival gangs of thugs You can not blame people for moving. Did drugs force people to vacate? In any case they did a study on how to bring NORTHTOWN back

https://taubmancollege.umich.edu/sites/default/files/files/mup/

capstones/NorthTown-2015-Final.pdf

In the end,the insurance polices made it lucrative. The policies that covered the houses were part of the purchase price... Therefore the money was retrievable even if the house was no longer valuable...Of course retrieving money through arson is illegal , but it worked. That is my theory: NOT saying who did it. Not saying anything... letting the podcasters talk. https://anchor.fm/cedgpodcast/episodes/Chaldean-Mafia-True-Crime-Story-em9uoe or scroll down to see more on Grixdale here https://www.downtownpublications.com/single-post/2018/04/24/organized-crime-then-and-now-in-metro-area CLICK ON MAP TO ENLARGE

More on Grixdale here :http://motorcitymuckraker.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Screen-Shot-2014-06-05-at-8.04.01-PM.png

Huh?? Maybe there needs to be an explanation on this one. If your church or job formed a corporation and brought up houses and then was able to resell it to you with the mortgage covered-- that would quickly settle an area. That is how they did it in the old country. The money you paid into the corporation was invested so it grew. The investments were made. The investments were raffled off. Its your turn You got a house and there is no loan or interest to worry about...

in this instance shareholders got a property under this system : all you had to do was maintain what you got.

The occupier would not feel tied to the property and could move on easier- let the corporation resell it.

If the corporation could not sell it, they could claim the insurance money.

The image below links to a slideshow

Typical burned out 4 square built in the mid 1920s .

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/eerie-images-of-detroits-most-abandoned-neighborhood/ss-BB1cbqO7?fullscreen=true

How to explain the worst damage? Maybe you do not. Maybe you try to fix it .

The following two stories, 10 years after Occupy

explains how others tried to fix Grixdale. Pay attention.

Its a tale: It will take @42 minutes to read...

BY ANDREW

FEDOROV

03/19/2018 originally written for WWW.THESMARTSET.COM

PHOTO BY Photo

of oil drum moving courtesy of the author Andrew Federov. Other photos are screenshots of Google Maps All

artwork created by Emily

Anderson. BOLDFACED items are updates in 2021and open into a picture (example : addresses of locations in boldface ) courtesy of this blog (2021)

In

late January of 2015, a tree stood wavering on the edge of Detroit’sburnt-out Grixdale neighborhood. A loud, old engine revved. A

100-foot rope tightened. A car strained forward. The tree followed,

snapping and dropping into the overgrown yard of an abandoned house.

A group of bearded men looked on from the front yard of a

fire-ravaged structure across the street. Satisfaction and relief

filled them as the final rays of sunlight scattered into the gray

horizon. They had lost two ropes and a chainsaw in bringing down the

tree, but they comforted themselves with the thought that the

abandoned house and the surrounding telephone lines stood

unharmed.

They

were pretty far from Detroit’s refurbished downtown. Years ago,

this neighborhood had succumbed to the rot brought on by the crack

wars. Inhabitants fled, homes were torched, and the long blocks, once

designed for cars, were left sparsely populated. In 2015, it

remained largely abandoned. Sometimes, there were residual

flare-ups of violence and theft. Some ways down the road, there

remained a crack house. In this quiet, largely forgotten place,

however, adjacent to the vistas of empty lots, under the canopy of

old-growth trees, there was a new community growing. They lived

amongst the neglected red brick houses and chose

to call themselves Fireweed, after the pioneer plant species that

takes over the landscape after a forest fire.

These

men were specimens of that community. They and other Fireweed

residents rejected the traditional sources of basic amenities. For

light, some installed solar panels and some illegally hooked into the

city’s electricity in horrifyingly jury-rigged ways. The rest

scavenged for candles. At night, they stumbled around with

battery-powered headlamps. A few houses ran water, illegally, from

the city system. The rest lugged their water in plastic jugs from

those houses. The only house that was both associated with Fireweed

and fully wired into the grid was that of a chiropractor, Doctor

Bob Pizzimenti, a self-described “recluse” in the community who

claimed to enjoy watching its developments from afar. All but Doctor

Bob’s house were heated with wood stoves.

At

the site of the fallen tree, William Phillips ran up through the new

darkness and began pulling at the massive knot around the trunk.

Chris Albaugh began gathering the tools. Multiple SUVs, bumping up

and down under the influence of their blasting hip-hop, slowed a full

minute longer than usual at the intersection to stare at the

white men running around with axes. Hunter Muckel jumped out of the

little red Toyota and slipped the other end of the rope off of the

car. He walked over to William, grinning. After a few minutes, they

got the rope off the tree. “It’s like a Chinese finger trap,”

Hunter said as the rope slithered off the trunk.

They

could give Charlie Beaver his rope back, though not his chainsaw, and

the whole community would have firewood. The first urban

lumberjacking mission by Fireweed’s engineering committee had

been something of a success. But what kind of success was this? Why

did they choose to live in this way, in this weird, wild land,

between prosperous zones that burned without responders? Why did they

spend their days chopping trees for janky, jury-rigged wood

stoves, rather than buying into electricity and central heating? Why

did they choose to live on the edge of desolation?

•

I’d

been here once before. On the cusp of the previous fall, I’d

hitchhiked out from Ohio. The stories I’d heard lured me back;

stories of train hoppers and men walking across savage America

without any destination in mind. There had been one vagabond veteran

who’d returned from the war without a plan, without a home, who’d

wandered the midwest on foot, sleeping in fields and barns, and

draining the long-forgotten booze stashes of forsaken rust-belt

hotels. When I came back, I found that these characters were just

the superficial ephemera of Fireweed. They’d flittered away as

the cold Detroit winter descended and the easy pleasures of summer

evaporated, but the core that remained was much more committed,

passionate, and confusing.

illustration created by Emily Anderson.

Fireweed

was not ideally set up for winter on Lake Huron.(too close to Canada) Even in the

summer, the smell of burning wood — the smell of coals and

scorched, carbonized earth beneath the bonfires that served as

gathering places — had permeated the neighborhood. In the winter,

whatever house you walked into, your nose and lungs were assailed by

the trapped smoke of the wood stoves. I’d noticed this as soon as I

got there. It was hard to miss.

I’d

gotten off the greyhound not long after New Year’s day, caught a

city bus from downtown to Golden Gate, Fireweed’s main street, and

pretty quickly made my way up to the living room of

169 West Golden Gate, the only building legally owned, at the time, by

Fireweed.

(See Green house below)

4 square style WHITE HOUSE/Occupy House (MURALS) 149

w goldengate details on regrid.com

WAS HOME TO ZACK

(NEXT ARTICLE)

The dark green

house (aka bottle house ) at 169 west golden gate is on regrid.com

Parcel ID 01006360

|

169 W GOLDEN GATE owned by Fireweed in 2015 |

taxes in arrears in 2021

|

|

|

Bottle House description :

There were blankets on the walls and a wood stove took up much of the

space. It was a big steel barrel turned on its side and mounted on

bricks, with a door on the front, a few logs inside, and tubing

running up through a hole in the window, carrying smoke from the room

and into the atmosphere. Sitting there, I reacquainted myself

with three people. They reminded me that there was something other

than outlandish stories which had brought me back: I was thrilled by

the virility of experimental lives.

I’d

stayed with Sara last time. She had widely spaced eyes and wavy brown

hair, and she’d come here after finishing a marketing degree. Her

homestead was Slide House (160 west golden gate)

across the street. A former goat house and bike shop under Dr

Bob) , it was the least conventional looking home on Golden Gate, with

its boxy shape, flat, leaking roof, fully graffitied exterior,

and a twisting, yellow slide, salvaged from a playground, attached to

the front.

Slide

House August 2015 (160

w golden gate)

pay no attention to google addresses shown in maps Using regrid .com to verify

Google Maps Screenshot @2015

Slide

House in 2019 Google maps screenshot

160 w golden gate

Sara

would

light a few candles inside to illuminate brown corduroy couches with

cats lounging on them. In the center of the house was another

wood stove.

I’d

met Shane standing around a fire. He was an impressive figure: tall,

lanky, blond, with a big curly beard and, often, an axe in his hand.

He’d been there, not exactly from the start, but pretty close. I

learned some of Fireweed’s history sitting in that dark, smoky room

with him. There’d

been a few people squatting on the street as early as 2009 and

rumors, as rumors do, had spread. Mars

Noumena bicycled 2,000 miles from California to join what he thought

was a much more developed community. Not long after, when the winter

of 2011 set, Mars invited Occupy Detroit to move from Grand

Circus Park to Fireweed. They took over the white house on the

street,(149 w Golden Gate) which became known as the Occupy

House (later the White House -with occupants again ).

It was used as a neutral space, not permanently occupied by anyone.

The Occupiers built a library, a free store, a dishwashing station, a

kitchen, and a shower area open to the community.

But

it couldn’t last. “It’s very difficult to have a fully livable

home that no one lives in,” Shane said. “With all the demand for

living spaces, it’s very hard to keep that locked up.” By the

time I got there, Occupy House had been occupied for years by Mary,

who kept her gray hair in dreadlocks and ran a shifty business

from her living room. She lived with her daughter, a group of mostly

local young men known as “the block boys,” and a pack of dogs.

Mary and Charlie Beaver, the scruffy, quarrelsome, stubborn, kind,

and idealistic gentleman whose chainsaw had jammed mid-tree,

constituted Fireweed’s older contingent.

Shane

never saw the Occupy era of Fireweed. Not long after those occupiers

moved on, his life changed. His job as a manager in the Hilton I.T.

department was outsourced and he used his severance bonus to go

traveling. Six months into his time bumping around the country,

meeting people and visiting friends, he met Zack,

a Fireweed resident,

at a Philadelphia bus terminal. He spontaneously changed his ticket

to a Detroit-bound one-way. When he got there, he moved into

intentional

house 159 west robinwood

and he’d lived in the same room ever since. At the start, he had a

roommate named Coconut, who ran a weekly writers workshop in what’s

now the toolroom and expected people to go barefoot despite the

abundance of “Detroit diamonds”: the glass shards which

litter the streets.

“There

were drunken brawls, multiple times a day sometimes, out in the

middle of the street, people dragging shotguns and yelling up and

down, like, literally absolutely crazy,” Shane recalled of those

early Goldengate days, “people getting shot, people getting stabbed

constantly, over and over and over again.

(Shane describing the area as the Grixdale Neighborhood

would be more accurate. The whole area not just West or

East Golden Gate was affected by crime.) "

"It was ridiculous. It

amazes me that people like Coconut were alone in their little zen

space not allowing any of it to hit them.” The final stroke for

Coconut was the theft of his bicycle. He left. Shane stayed.

Most

days, Shane went out to chop trees and cut rounds. If ever while

walking around looking for suitable trees he saw anyone, he’d wave

and ask how they were doing. If they offered to help, he’d say

maybe they could carry wood later. He seemed to enjoy the solitude of

his work

Hunter

Muckel, on the other hand, was a recent arrival. When he’d moved

in, in early August, Detroit had been flooding. Of all the people who

lived in the community, he’d taken the least-likely path to end up

here. A few years before, when he’d enrolled at the University

of Indiana, Bloomington, he’d thought he’d be a business

major. Clearly, he wasn’t an anarchist at that point. “I wasn’t

a Republican anymore, but I was a Libertarian. I considered myself a

Libertarian,” he said. “Then Occupy happened. I went down there

and, being the good fiscal conservative that I am, I saw them

handing out Coca-Cola hats and was like ‘you guys are handing out

corporate sponsorship and you’re talking about not liking

corporations!’

“They

said ‘Hey! Stop yelling at us from the sidewalk and come over here

and talk.’ We started talking, and I realized that the Occupy

movement really did align with my fiscal conservatism.

illustration created by Emily Anderson.

“From

then on I was like, you know what? I’m going to start showing up

here every day. My first thought was this really egotistical thought.

Because I liked the conservative part of the Occupy movement. I

wanted to influence Occupy Bloomington in a way that wasn’t

radical. I didn’t want them to be radical. I wanted them to be

fiscally conservative.”

It

didn’t quite work out that way. “The Occupy movement opened my

eyes to this totally other way of living,” he told me, his eyes

alive with remembered passion. “I started seeking out new ways to

look at the world. I stopped smoking pot for Occupy, man. I was

serious about that. I didn’t feel the need for it. I was tripping

the whole time. I was tripping on Occupy. I learned about intentional

communities there. It was incredible. To some extent, I always knew

that we were fighting a failing battle and that we were going to get

shut down eventually, but I didn’t care. I just wanted to show as

many people in the limited amount of time that we had what my eyes

had been opened to.”

He

began to come down from his trip when general assemblies began

to crumble into a few people giving routine speeches. He split off to

join the “getting shit done committee.” Its members did what they

thought could help without necessarily talking about it. He began

to reassert his family’s blue-collar roots and rediscovered a

consciousness in action. Rather than the airy sense of accomplishment

provided by expounding theory, he demanded thoughtfulness in every

act and about the hard facts involved in fulfilling needs.

He

graduated with loans weighing on him. He wanted to play music, to

visit Armenia and Palestine. He thirsted for adventure, but his

father’s invocation of financial responsibility hung over him. A

debt, he thought, was a claim on his freedom: it would allow others

to enlist his time until he had rid himself of it. So he scrounged up

work in Detroit. “I rode in with my motorcycle the day before

I had to start my AmeriCorps job.” But Hunter missed the high of

Occupy. He missed that sense of discovery and the sense that what he

was doing mattered. He started asking around about intentional

communities in Detroit. When he found Fireweed, he started spending

most of his free time there. Then he moved in.

•

Eventually,

I asked where I could sleep. Sara pointed me to Intentional

House(159 w robinwood ) , behind Slide House (160 w golden gate ) ONLY one street over on

Robinwood.

It was stewarded by a strange man who went by Irie. He didn’t live

there anymore, though. He lived in the Universe

Building, a massive warehouse with heat, running water, and

electricity a few blocks away, which Fireweed sometimes used as a

meeting space. He’d

picked up his name while living with Rastafarians in Kalamazoo.

Before

this part of Detroit had been abandoned, Intentional House must have

been a split two-family home. Irie had decorated it with his

collection of quaint and offbeat antique furniture. It looked like

part of a ’50s nuclear test suburb. The one operable wood stove sat

in a room on the first floor with very high ceilings and an

entrance shielded by blankets to trap the heat. Whatever you did,

though, whatever you tried, in winter, Intentional House was at least

chilly. But you turn numb to the cold.

I

had two housemates: Chris Albaugh and William Phillips. We slept in

the little room with the high ceiling and the stove. Chris slept on a

cot to the side of the stove, William on a couch, in the coldest part

of the room, against the back wall, and I in the middle in a pile

of blankets. In the dark of the room, we talked while lying

down. I told them about myself, though there wasn’t much to tell.

They told me about themselves, and there was plenty.

Chris

had told himself that he wouldn’t be an adult until he could grow

his own food. When Occupy Eugene happened, he dropped out of a lot of

his classes at the University of Oregon, stopped paying rent on his

house, and moved to the encampment. He went on to visit other Occupy

encampments and walked with Walkupy, a traveling cross-country

encampment, for two weeks. Occupy left him disillusioned with the

idea of protest and revolution in a classical sense. Now, he

wanted to work toward revolution one step at a time, acting on a

personal level. He wanted to build an alternative society so when the

old one collapses, people will have somewhere to turn. He’d moved

to Fireweed on Christmas Eve, about a week before I got there, with

hopes of working on an urban farm.

He

was an intellectual, a dreamer. He’d spout off Walden quotes and

makes small talk about anarchist theorists. “My food security is a

radical method to liberate myself from my current paradigm,” he

said, “but, to an outsider, I’m just growing food, I’m feeding

people. Farming is kinda

radical but it’s not really that crazy. Maybe it’s in a slightly

radical environment, but still, I’m just growing food.”

William

looked like Doctor Watson would look after a couple months living in

the woods. You could still hear his North Carolina accent. He’d

joined the Navy on the heels of 9/11. “They lie to you all through

the recruiting process,” he said, so he got out as soon as he

could. In 2009, he got involved with Iraq Veterans Against the War.

He began thinking and decided that “government is one of the root

causes of war and one of the best ways to fight it isn’t so much to

fight it but to drop out of it and quit feeding it.” The previous

May, he’d found Fireweed on a Libertarian website and had come out

to Detroit.

In

his life, he tried to avoid assumptions. Sometimes this took a toll

on his capacity for optimism. He found the hippie aspects of the

community off putting and unproductive. “Will expects there to be

social norms, to some extent,” Hunter told me later, “he expects

you to not be fucking nuts, which sometimes doesn’t happen around

here.” He tried to not let this stop him from helping. With a shy

smile, he told me, “I never really tried to spearhead a project,

but if they need help with something, they know where to find me.”

Then he chuckled.

The

fire went out sometime in the night. In the morning, we woke up

freezing

The

next night, we had trouble getting the fire started again. Once we

did, Chris defrosted his feet in the stove. We had some pasta with

canned tomato sauce and got into our sleeping arrangements. That

night, in the dark, we told jokes.

“Why

isn’t there a hunting season on hippies?”

“You

ever try to clean one of those things?”

“How

do you know if a hippie slept on your couch?”

“He’s

still there.”

“What’s

the difference between a girls’ track team and a band of pygmies?”

“One

is a group of cunning runts.”

The

next morning it was still fucking cold.

A

few nights went by like this. William began to develop an intense

cough and Chris found a completely frozen lemon.

photo by ANDREW FEDOROV

We got lucky, not

long after that, when Hunter offered us the opportunity to move into

Bottle House.

The

presiding spirit of the Bottle House

was Cookie, a sprite-like local who decorated the house with

astounding art which revealed itself if a lucky eye caught it in the

right flash of sunlight. At one point, Hunter had moved in too.

Bottle

House (169 w golden gate)

was the only building on West

Golden

Gate

that could rival Slide House (160 w golden

gate

)

in its inspiring visual oddity. It

was known for its friendly orange-and-green paint job and the many

colored bottles encased in cob that served as stained glass windows are

still there (169 W Golden Gate )

Its shelves held Edward Lear’s collected nonsense, assorted

classics, a Thomas Edison biography, practical engineering

books, and a collection of Zane Grey’s novels in matching red

hardbacks with titles like Wilderness

Trek, Western

Union, 30,000

on the Hoof,

and Majesty

Rancho.

That

winter, Cookie left Hunter alone in the house. “She comes and goes,

especially in the wintertime,” he said; “She has a million places

to stay that are much warmer.” Not to say that the Bottle House

wasn’t relatively warm. Hunter’s dad had brought him plenty of

wood, which he kept in the basement, and the stove distributed heat

well. “I feel the need, as a new person,” Hunter said later, “to

welcome other new people.” One morning, he unlocked the door and

left for work. Chris and I piled a wheelbarrow with blankets,

pillows, Chris’s cot, my backpack, and some food. It took a few

trips through the snow to get everything from house to house. I

stuffed my coat pockets full of tea bags.

That

night, no smoke rose from the roof of Intentional House.(159 w

robinwood)

Chris

and I enjoyed the warmth of Bottle

House ( 169 w golden

gate)

and William spent the night at the Universe building. At dusk,

Intentional House (159 w robinwood) was broken into, rummaged through, and robbed.

Chris and I noticed the next day that the back door had been kicked

in. Without venturing a look inside, filled with fear that whatever

had entered hadn’t left, we walked over to the Universe Building to

tell Irie.

“I’ve

dreamed so long and now I’m being crushed by my dreams,” Chris

moped as we walked. Up ’til then, I’d thought that idealism might

have kept people going in this climate, under these conditions. The

stakes and the risks hadn’t seemed so stark. You might get cold and

you might be hungry, and maybe you’d even get sick, but you’d

probably be alright by the time summer came around. That night,

however, as far as we knew, Chris might have lost his laptop, his

bike, and much besides. In that moment, at least, he’d lost his

sense of security. Idealism had to be part of what brought him

here, but it couldn’t be what kept him and the rest of the

community, which routinely suffered these sorts of setbacks, from

leaving.

When

we told Irie about the break-in, he told us that his phone had been

buzzing with texts the previous night and early in the morning from

someone who’d said he’d wanted to stay at Fireweed. He figured

that the texts had to come from the person who’d broken into

Intentional House. He wanted to report it to the police, until he

remembered that, for reasons he wouldn’t make clear, he couldn’t

make a police report. William, Chris, and I refused to make the

report. It probably wouldn’t have made a huge difference. People at

Fireweed estimate that, on average, it takes the police about five

hours to respond.

Irie

took on the role of detective, trying to reason his way through the

crime on the way to its scene. William, naturally enough, joined in

as his Watson. I trailed along. The house was a manic mess. There

were two pairs of footprints outside, the furniture and any unsecured

objects were scattered, drawers hung halfway out of every wardrobe.

Chris’s laptop, Irie’s chainsaw, and a bicycle were gone. Irie

stalked about, trying to figure out what happened and who could have

done it. He went through each room tossing out theories with abandon.

At one point he accused William, though he himself could act as

William’s alibi. So William gathered his clothes and welding mask

and moved to Bottle House (169 w golden gate).

Irie

called the person who’d texted him and found himself on receiving

end of a two-hour diatribe. The man on the other end of the line

traced his descent from Atlanteans and explained that he was a

reincarnation of William Wallace and Nikola Tesla. Irie

intermittently interjected “uh-huh” while shaking his head

in disapproval and maintaining a dazed, confused, and eerie smile.

Mars and Shane figured the culprits were probably crackheads from

down the street. Irie remained irate and, ultimately, unsatisfied.

One learned to live with mysteries and loss.

•

According

to legend, the first squatter at Fireweed was Hippie Mike. It’s

likely there are no other Hippie Mikes in the multiverse and, almost

certainly, there is no other place where Hippie Mike could be Hippie

Mike. Mike is unmistakable. He seems like the sort of person

that could only exist through a single chain of events. His

birth, however, was a regular one. It took place in Waterford, about

40 miles from Golden Gate street. When he turned 18, his mom kicked him out

and he discovered the country, hitchhiking. In that time, he worked

as a short-order cook in four different Waffle Houses across America.

His favorite was in Arizona and, in quiet moments, he dreamed of

returning to the beautiful, arid state.

About

seven years before I got there, a girl brought Mike to a drum circle

at Doctor Bob’s. He took a wander around the neighborhood and

decided that he’d found his spot. Where others saw risk and decay,

Mike saw free housing. In the wake of his monumental vision, a

community was born.

Mike

was the first person to show up to the weekly community meeting and

potluck at the Universe Building. His monk-pattern balding scalp was

bobbing and his scraggly beard spread out to conform with his smile.

He talked, with his characteristic mumble-slurring, about his

favorite subject, “cannabis caregivers and patient providers.”

His dream was to become a certified “cannabis caregiver” and to

grow his own weed, but this was foiled by his constant lack of

capital. Eventually, the rest of the community arrived and the

meeting started.

Fireweed

theoretically functions on a consensus structure, similar to Occupy,

in which the community discusses an issue or a proposal until all or

nearly all of the members come to an agreement on it. In actual

practice, people announce and explain their intentions and projects

at the weekly meetings and in regular conversation and whoever

supports them consents to help.

Mars

led the meeting, as usual, though he no longer lived at Fireweed. He

ran a pedicab company in downtown Detroit and he’d moved to be

closer to his work. He’d started shopping at Whole Foods but still

carried a large knife on his belt. Sara took notes, as usual, and

William was unusually empowered to speak by taking stock,

keeping track of the order in which people wished to contribute.

Hunter and Chris were as loud and talkative as usual. There were

others who talked. I kept quiet, mostly. Charlie Beaver was high,

instead of plastered, and unusually placid. The

only flare-up was the revelation that Doctor Bob owned Slide

House(160

w golden gate)

and

was considering turning it back into a goat house.

Sara snapped “how many of you have actually raised goats before?” About a quarter of the hands went up.

2021 UPDATE

Dr

Bob no longer owns Slide House. He owned 12 properties, CREATING HIS OWN MINI NEIGHBORHOOD

The golden gate/ robinwood situated properties ARE almost back to back and mostly connected. One could walk next door to borrow a cup of sugar.

Current Dr Bob holdings in Grixdale 2021 are 11 ... not counting the business Pyschedelic Healing Shack (formerly the

Innate Healing Arts Center)

https://www.metrotimes.com/table-and-bar/archives/2007/05/30/wellness-on-woodward

---slide

house at 160 w golden

gate

has lost its slide but

is even cuter now (but Dr

.Bob

sold it )

The

people who lived in it and ran it as a bike store at least managed to

be kind to the next generation –" target="_blank">https://www.facebook.com/GoldengateRestorationProject/videos/427577157265356 the kids

. See video here:https://youtu.be/VdIewb5afnY

The

following were

Fireweed Squats. Dr. Bob was quite generous and let the fire weeders both pre and post Occupy,

live rent free in

about half of his landbank properties:

167

w

robinwood

Burned

Out

/

159

w

robinwood

Burned

Out

Intentional

house

151

w

robinwood

empty

175

w

robinwood

empty /

181

w robinwood

Burned

Out

150

w golden

gate

Burned

Out

176

w golden

gate

decent shape

168

w

golden

gate

empty lot

/184

w golden

gate

empty lot

200

w golden

gate

empty lot

160 w golden gate (Slide house)

18700 Woodward is psychedelic healing shack

https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/michigan/psychedelic-healing-shack-mi/

Fireweed in Action

Afterward,

there was a smaller meeting about how they ran the meetings. This

might sound like the birth of redundant bureaucracy in this fledgling

society, but it brought out something important. Fireweed was

disproportionately male, white, and nonlocal, in a city that is 83

percent African American and, like most cities, has a basically 50-50

gender distribution and a majority local population. So why were the

members of this community different? I suppose it’s to be expected

that an unusual project will attract people from far away. But why

white and male? And, if the members of the community didn’t

reflect the people around them, how could they benefit Detroit, or

even the Golden Gate cluster or larger Grixdale community, as well as themselves?

At

the end of the night, Sara threw out a single soggy White Castle bun,

the remains of Mike’s dumpster-dived contribution to the potluck.

“Hey! Dig that up out of there!” Mike shouted. “I’m a

freegan. I live on that stuff!” The only thing he got consistently

mad about was waste. One time he took a few vegetables out of

Fireweed’s garden and traded them for a beer. When Shane found out,

he sought out Mike, who promptly offered him some. Shane simply

nodded, took the bottle, and turned it upside down.

Winter 2014-2015

Hunter

and Chris didn’t stick around for the drama of Mike’s buns. After

the meeting about meetings, they walked over to an abandoned,

remarkably well-preserved house on Robinwood. It had clung to

all its carpeting, and, instead of the holes left by scavengers

yanking out wiring to sell as scrap copper that decorated many of the

walls in the neighborhood, it had Dora the Explorer stickers and

other remnants of a happy family life. The man who’d started

squatting here not long ago, Moe, had a couple things in common with

this house. He’d seen and lived through the turmoil and changes

that rocked Detroit. His family had lived here for generations. That

winter, unlike the rest of us, he didn’t have an out. Hunter had

supportive parents, Chris had a mother in a warmer climate and

periodically thought out

trying to find money for a bus ticket out there, and William was

thinking about leaving later in the year. Hell, I was going to be

gone at the end of the month. Moe didn’t have an easy exit.

Except for a brief interlude in the military, Detroit was what

he knew and had always known. This place, its challenges, and the

hustle that it took to survive weren’t new to him.

Fireweed

surprised him, though. He’d started stopping by Bottle House after

finishing a temp gig distributing flyers around the city. He’d play

a game of chess with Chris, and most of the time he’d win. One day,

Hunter gave him a lift to the store without asking for anything

in return. “Why’re you doing this?” Moe asked. “If I buy

a pack of cigarettes, I’ll give you a couple cigarettes and

we’ll be good.” “If

you want to give me a cigarette, I’ll take a cigarette,” Hunter

said, “but you don’t have to give me a cigarette.”

“I

don’t get it,” Moe said.

Image by Emily Anderson

“That

comes from living here, man,” Hunter reasoned later on. “That

comes from living in a city where you take, take, take, and there’s

scarcity so bad that you need to take, take, take.” Maybe it wasn’t

his place to say it, but it’s a conclusion that’s hard to miss.

The difference between us and Moe, between people who, at one

point, at least, had a choice about whether they were going to live

here or not and those who didn’t, came out in the way we looked at

the world. But these weren’t insuperable barriers, and the longer

the residents were around each other and the more time they

spent here, the more muddled their views became. Moe was, for the

moment, willing to try Fireweed’s paradigm. Someone had stumbled on

four steel barrels. They’d contained chemicals of some sort at some

point, but, with a little work, they would serve beautifully as wood

stoves. Moe was down to put in a little work if it meant he could be

a little warmer.

The

stove that was to be installed in his house had a new design. It

stood upright rather than horizontal, giving it a flat cooking

surface on top. Shane, after years of living through Detroit winters,

in a cautious, conservative mode, objected to such experimentation

because the alternative to success was allowing a house to freeze, or

burn. Moe was willing to try it. We rolled the four salvaged

barrels down the middle of the snowy streets, kicking them to keep

them going, sometimes leaning in to give them a steering push. In

Charlie Beaver’s backyard, we filled them with wood and paper and

lit fires. At first, the inflamed chemicals rose in a cornucopia of

color towards the sky, then, pure black smoke began to spew out in a

steady geyser until the barrels had been burned clean. Hunter

operated Charlie’s angle grinder to cut holes for the chimneys and

doors. One barrel went to Moe, one to another house in the community,

one was used as material for stove doors, and one was a spare stove.

We

rolled Moe’s barrel over to his place and shoved it up the stairs

to the room in which he planned to sleep. To prop it above the

carpeting, we carried over cinder blocks out of a burnt-out house

down the street. I dropped mine a couple times. I’d never carried

something that heavy that far before. We had to chisel out a hole in

the brick wall of that room to run the chimney tubing out. It would

need a bit of insulation around the tubing. Heat was a negotiation.

After more than a bit of work, it was ready. When Hunter and Chris

walked over that day, after the meetings, they ran the tubing through

the wall, and with Moe they built a fire. When the stove worked,

Moe’s house was warm. When William and I got there a couple hours

later, we threw off our coats. It was almost worryingly warm, but it

worked.

By

this time, the residents of Bottle House, Hunter, Chris, William, and

I, had begun to think of ourselves as an engineering committee. Our

meetings were in nearly constant session. Each day, it would start at

just about ten a.m. over eggs and coffee. By then, Hunter would

have been up for hours, since sunrise. Chris would pop up from

his cot mumbling about some idea he’d had in the night. William

would drowsily rise from his pile of sheets near the hanging blanket

that insulated and isolated the main room of the house. We’d spend

the nights talking under the one electric bulb which was hooked up by

a discrete, overhead wire to a car battery in the attic charged by

the solar panels.

People

who don’t have much electricity tend to talk more. They talk about

how to fix stoves, how to heat water, how to pivot solar panels.

They dream about bike-powered electricity and using magnetic

fields around electrical transformers to get power. Sometimes, they

joke about converting the methane in the city sewer systems to

electricity and buying plots of land on which to farm and in

which to bury secret storage-container homes. Oddly enough,

for people who hardly had enough electricity to consistently

power a lightbulb, much of our talk, when not about these

outlandish engineering projects, was about half-remembered T.V.

shows.

We

talked a lot, but we only got things done sometimes. Next to Shane’s

shining example of individual industriousness, our achievements — a

couple stoves here and there — were nearly nonexistent. Sara was

worried that Shane was overworking himself. Chris idly suggested that

if he asked for help, or even told people where he was working, he’d

get help. Sara suggested he take some initiative. Hunter agreed.

After some deliberation, we decided that the next day, with the help

of Charlie Beaver’s chainsaw and Hunter’s car, we would pull down

a tree.

•

The

morning after the tree fell was a Sunday. It was a peculiarly warm

day. Rather than the seemingly permanent frost and snow, the

residents woke to the sound of rain; instead of balancing on ice,

they sunk into fresh mud. In the greenhouse next to Slide House it

was even warmer than outdoors. It was the first time in a long time

that anyone could be more than a couple feet from a stove wearing a

t-shirt and jeans. The Ohio boys hosted a work day that day in

the greenhouse. They, Nathan and Josh, had joined Fireweed a little

before Hunter had. He saw something of himself in them when he

arrived. In the dynamism of this community, he saw not a blank slate,

but the raw materials needed to build a society that he could

understand, a society for which he could feel responsible: a better

society. He saw a wealth of material and a lack of preconceptions.

The boys saw that too, but their path to Fireweed was radically

different.

Nathan

was born in Owensboro, Kentucky, a town most famous for producing

NASCAR drivers and Johnny Depp’s wish to flee. His parents were

poor, transient, southern Baptist fanatics. “Being openly gay

was not in the cards at all,” he explained. Nonetheless, in an act

of near-futile bravery, he came out in the seventh grade while in a

psychiatric hospital for what his mother said was depression. His

family quickly decided that he should be sent to straight camp. Their

local church gathered the money to send him away within two days. He

spent his days either in solitary confinement or having olive

oil poured on him in a chapel. Most of the time he closed his eyes.

He signed the papers and became a statistic: “a recovered

homosexual.” When I met them, he and Josh had been together for

eight years.

“You’re

tied to this grid and when it goes down you’re gonna be screwed,”

Nathan declared in the greenhouse, his Adam’s apple bobbing in the

wake of the vibrations of his nasal voice and his eyes glaring with

fighting intensity and a hint of fear. Josh offered the smooth and

genuinely friendly smile of someone with a broadcasting degree. Two

years before, they’d quit their opulent lifestyle in Cincinnati,

broke off communications with the majority of their friends, sold

most of their possessions, and bought two cheap acres of land next to

“a cop-infested highway” in Ohio. They moved into a converted

storage container, something akin to the house in Tron, and started

farming.

They’d

heard about Detroit’s fallow land and decided to expand their

farming operation. When they first got here, they moved into the

Bottle House. Not long after, they moved a ways away to an abandoned

mansion on Chandler street, near the headquarters of 7432

Brush St. aka Michigan Urban Farms.

“I sang on the weekends,” Josh said with a pained squint to his

eyes, “At the same time as I was advertising for my first show in

Detroit, someone broke in and stole all of our music stuff.” I

asked if they’d ever got it back. Nathan laughed a little. He used

to drag race and had a fondness for risk and trouble.

Now

they were living on Robinwood and were part of the community again.

On this day, the community came together, just like in the summer. We

dug a trench along the bottom of the greenhouse, which the boys would

go on to fill with water. When we were done, William and I walked

over to Doctor Bob’s cafe with the Ohio Boys. They were helping

Doctor Bob out over there, and he let them feed us some soup. When we

finished up, William and I walked over to the site of the felled

tree, where Hunter and Chris were bringing axes down into rounds of

wood.

Image by Emily Anderson.

“Burning

wood is not a sustainable solution,” Hunter said between swings.

There weren’t enough axes now, so he and Chris traded off, as

William and I ran back and forth depositing armfuls of wood in a

light blue trailer, fabricated by Hunter’s dad, attached to

Hunter’s car. “With the number of people we have, we can burn

wood and be fine, but you can’t have everyone everywhere do it. It

wouldn’t work.”

When

the wood was piled high on

the trailer, Hunter slowly and carefully backed the car down the

one-way street and, just as slowly, drove back to Goldengate. We left

it in stacks in front of Slide House. There was enough for everyone

to stay warm for a long while.

•

A

few days later, the engineering committee invited the community over

to Bottle House for pasta with homemade alfredo sauce. Chris and I

had walked past the city border the night before to a supermarket in

one of the suburbs to buy the fancy cheese for the sauce. Brian, who

was then living in Slide House, came over first and strummed his

guitar and spoke of the sorrows of a jailbird nomad with a pregnant

girlfriend. Brian brought his dog, Jaeger, who he’d had since

puphood. Jaeger looked like the Hound of the Baskervilles, a big

black dog with massive jowls, but had the personality of a friendly,

drunken socialite. He’d followed Brian through the crowded

streets of New Orleans’s French Quarter and countless

cities through years of rambling, without a leash. Once, Jaeger

bit a cop who’d threatened Brian,

and Brian wrapped himself around Jaeger. In his South

Carolina-Colorado accent, Brian had begged, “don’t shoot my

dog.” He still slept wrapped around Jaeger.

Chris

cut off the bottom of a Faygo bottle to make a bowl. He joked that

the other half could be used for a gravity bong. Hippie Mike

soon wandered in. Sara and Shane eventually joined us. They

crowded into the small room. Most found decent seating. Hippie Mike

sprawled out on the floor next to the stove, his legs splayed in

either direction. The conversation soon turned to the questions

that had been on my mind since I’d got here. Why were they here?

Why did they stay?

“I

hitchhiked around the country for years because I didn’t want to

put into their system,” Brian said. “That was the smallest

carbon footprint I could think of.” He wondered if an urban farming

project and a set base was really the solution. He wondered whether

they would achieve anything substantial here. “We need to wake

up one day and see a collapsed system,” he said. Sara

admonished him for his pessimism. Brian explained that he was worried

about the society his child would be born into. He wanted to

show his kid a different way of life. He wanted her life to be

devoted to living, rather than to mindless, grinding labor for

somebody else’s cause.

“I

get it,” Chris said. “I get the pessimism. I understand my

reality but I know if I stare too long into that darkness I

won’t survive. I don’t give a shit what the truth is, but I

believe what helps me get out of bed in the morning. I can only

live with the hope that things will get better.” He was just

ramping up. “Just because they tell you that you have to go to

college and then get a job and work 30 years and then find a

wife and a white picket fence and then retire doesn’t mean

that that’s what you have to do. You have the freedom to live the

life that you really want to live, even if the system’s

opposed to it.”

“We

need to go out there and do it, and we need to get people to come

with us. That’s what’s important,” Sara said.

“You

can’t isolate,” Chris said, nodding. “You have to live in both

worlds at the same time. If you isolate yourself, you can’t

connect to the base you’re trying to educate. There’s a spectrum

of non-cooperation, right? There’s extreme noncooperation to the

point of like, you know, violence against the system. Whether

it’s mutually beneficial or whatever, we choose to cooperate

with the system by not shooting people, right? So there is a balance.

There has to be a balance. You have to change the system from

beside the system. Not within it and not outside of it, but

beside it. You’re creating the life, the reality, the community,

and the resources that you feel you need. That’s the only

change you can make, right? You can’t change the world, but you can

change yourself, you can change the people around you. Well, they can

change themselves, but you can lead them.” Chris liked to make

speeches; sometimes they were worth listening to. “It’s not

about the end solution,” he went on, heading toward a conclusion.

“It’s not about what form of government we’re going to

have. It’s about communities of people creating social

structures that are healthy, sustainable, positive, and beneficial to

them and their localized environment.”

Suddenly,

a sound shook the hanging blankets. The door opened with the force of

a windy winter night. A blanket lifted, and Tommy Spaghetti

entered the room. His smile was framed by white stubble, a black

mustache, dark gray sideburns, and playful black eyebrows. His hoodie,

splattered with many-colored paints, sat atop a blue bandana. The

American flag was stretched across the back of his black jacket

and his sleeves proclaimed in big blue letters, “USA.” The

tidiest parts about him were his plain brown corduroy trousers.

Tommy

used to sit on the roof of 169 w golden

gate

(Bottle

House) , playing his saxophone as a chorus of dogs howled at

the moon. When a developer

bought Bottle House from the city a while back and tried to extract

rent from the squatters, Tommy gave up the money he’d been saving

for a trip to China and bought it from him. But he didn’t

pretend to have any real ownership over the place. He had only

two requests

for the residents: “First, protect the grapes.” He had three

grapevines in front of the house. That was his number one

priority. “Second, clean the house.” That night, his conversation

was peppered with ’50s slang and the words “bro,” “man,”

and “dude.” He talked of playing benefits in Ann Arbor and

encouraged Hunter to come busk. Talk became superfluous when the

instruments came out. Brian had his guitar at the ready, Hunter

snatched up his left-handed mandolin, and Tommy grabbed drumsticks

and positioned himself over the steel barrel stove. They played

Tommy originals, featuring Hunter’s mandolin solos, Tommy’s

beautiful whistling, and an ever-impressive mouth trumpet. Chris and

I stomped along. The music, the joy, and the overwhelming sense

of community seemed like they might be the ultimate answer to

that essential question that nags at you in the coldest moments: “Why

the fuck am I doing this?” Almost everyone sat down. William hopped

about, looking like Donald Duck, trying to get out of his

raggedy weathered jeans, leaving on only his grey waffle-patterned

long johns and undershirt. His face was red behind his bushy beard as

he lay down in his pile of blankets.

Image by Emily

Anderson.

In

the coming months , summer 2015 Bottle

House (169 w golden gate)

would burn down leaving only Hunter’s charred mandolin,

Chris and William would move away, the Ohio Boys would split, and

Brian’s baby daughter would be born. Despite their plans and

their principles, despite the cold that seemed a constant, none

of them knew what the future would bring. They were focusing on the

present. Their situation demanded it. But they’d chosen that

situation. Their mission statement read, “Fireweed

Universe-City is a grassroots movement to realize a sustainable,

eco-friendly community of Universal Consciousness.” At first

glance, that “consciousness” bit might seem like mystical

hippy bullshit, but it can and should be read on a much more

practical, quotidian level. The people who ended up here had started

life as standard-issue Americans. At some essential pivot point,

they’d each seen that the fire at the center of our civilization, a

constant presence, evenly and surreptitiously distributed throughout

our homes through some sort of figurative and literal central

heating, unseen and unknown, was something that

demanded consciousness. They saw that the people leading lives

as part of entrenched civilization had lost control and given up

responsibility without knowing it. The flame had consumed them

without them feeling it.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/occupy-detroit-on-the-move_n_1133548

For

a lot of the people here, their moment of epiphany had been Occupy (2011-2012).

The movement challenged them to rethink everything. So they kept the

fight going even as the movement faded away and the terms of

engagement changed, because in some sense they couldn’t go

on without it. (The following link shows pictures of January 2015 from the effort aka the GoldenGate Restoration Project) Grixdale is the neighborhood ; Golden Gate Street is running through the heart of it.)

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.878405075515893&type=3

Bottle House is in the bottom left corner once link is accessed

There were still pockets of Occupy scattered

across the country. On a hitchhiking trip the following summer,

I popped by to see the remnants of Chris’s home camp in Eugene,

Oregon, and, during the Democratic primary in 2016, I heard

memories and songs of the movement shared at the Bernie marches

in New York which ended in Zuccotti Park. But the rest of the country

had moved on. When Trump and his cabal of one-percenters took power,

the networks of class-based resistance had faded. Fireweed was

an attempt to find a sustainable way to keep them going. Part of

that project was forming a community based on shared ideals. They

refused to idolize the amorphous ideals of a society that was polite,

civilized, comfortable, and numb. In discomfort, they discovered

a virtue. This left a void and inspired a search for grounding in

their approach to the most basic things. They had to know how

everything around them worked. After all their searching, they

found that the most basic elements are people, the most

basic technologies their relations to each other, and the most

important grounding an understanding of those around them.

“When

people ask what this place is,” Hunter had told me the first time

I’d visited, “whether it’s a commune or something, I tell

them it’s a community.” It was a community which could

foster the new fragile fire of this beautiful, crazy, radical space,

and keep it going by building stoves, installing solar power,

working harder, expanding knowledge, planting gardens, and

felling trees. It didn’t matter that the country could fall apart

around them at any time: They were in the process of saving its

essence. Maybe to fight the fight was to lose it, but they felt that

the fight, the sustained conscious effort, the experience of truly

living, was in itself worth it. So, why does a tree fall in

Detroit? It might be said that it falls to light a new flame. On

that night in January 2015, in between songs, Hunter leaned back,

gave a drowsy smile, and said, “the hardest part about the

zombie apocalypse would be pretending I’m not happy.” He was

dreaming of a moment when everybody realized that they had to fight

for the life they wanted.

Bottle

House sang itself to sleep.

•

The

morning after the reckoning in Bottle House, engineering committee

did not meet. Hunter was at work and Chris and Will were still

asleep. Fresh sunlight filtered through the bottles in the walls

and lent kaleidoscopic tints to the rising breath of the sleeping

men. The fire had died, leaving only a few embers, and a chill

set in. Not the brief slaps of frigid wind that might assault

you as you walk from one warm building to another. This felt

permanent. This was at the

marrow and seemed to offer the singular option of a stoic

embrace. The final embers smoldered. The stove demanded wood.

Denouement

By

summer 2015 the Bottle

house was gone.

There is a Google map time point that shows White house(formerly the Occupy House) next to Bottle house in 2015 with the wood that was cut winter 2014-2015...

The White House *formerly Occupy House at 149 Golden Gate) figures in the next and final story of Grixdale, Fireweed and the houses around Golden Gate street) see image below bottom left

10 years after Occupy

the following event signaled the end of an era The following 1 minute read comes from https://www.mlive.com/news/detroit/2018/09/man_killed_on_bike_in_detroit.html

Man

killed biking from Belle Isle took road less traveled

Updated:

Jan. 29, 2019, 11:15 p.m. | Published: Sep. 16, 2018, 1:00 p.m.

By Gus

Burns | fburns@mlive.com

Zachary

M. Zduniak ,aka Zack is a 28-year-old man

killed while riding bike on Belle Isle in

Detroit. After he died,

drums beat for him at night near Seven Mile Road in Detroit. Friends sat in a

circle smacking the skins of bongos and congas while drinking beer,

passing food, smiling, laughing, crying and sharing memories of Zack

Zduniak, a 28-year-old anarchist artist with unruly ginger hair. The one-time

suburbanite who attended Catholic private schools relished in his

daily bike rides to Belle Isle's unofficially named Hipster Beach on

the Detroit River.

For 56 days in a

row, friends say he pedaled the 28-mile round-trip trek to visit the

hidden beach on Belle Isle. He kept count of those trips, and had

been so many times, some friends took to calling him "the

unofficial lifeguard of Hipster Beach."

But after his 57th

consecutive trip, while riding back across the MacArthur

Bridge that connects the island park to mainland Detroit about 9 p.m.

Aug. 26, he was struck head-on by a car. Zduniak died hours

later, peacefully and surrounded by family, according to his mother. His death left

behind a long list of friends and loved ones shocked by how

fleeting his vibrant life was.

Zachary

Zduniak Facebook photo

Zduniak, since

about 2011, lived on 149 west Golden Gate (White House and for a while Occupy House) https://app.regrid.com/us#p=/us/mi/wayne/detroit/190425 in a community known as Fireweed

Universe City,

where artists and squatters have gathered for years with a focus on

sustainable living, anchored by the Psychedelic

Healing Shack,

which contains a chiropractor's office and a vegetarian cafe.

He didn't keep a

regular job, he didn't often have a healthy bank account and he

didn't pursue the traditional career milestones aspired to by

many young Americans.

It was most

important to Zduniak to be happy now, today, friends and

family said. And that's why he visited the beach so regularly. Weeks before his

death, Zduniak made an addition to his tattoo collection. Newly inked

words on his left bicep read, "A lust for life keeps us alive."

Zduniak liked to be

airborne, often launching himself from that makeshift rope swing

along the secret beach at Belle Isle with friends. While others

his age hunted for jobs or climbed corporate ladders, he reveled in

the cool Detroit River water, emerging with his long

hair clinging to his face and covering his eyes. "I'm at the

biggest party of my life," is a quote Zduniak's mother Julie

Jurban, of Clinton Township, placed in her son's

obituary. That's how she likes to imagine her son now, partying in the

afterlife.

Zduniak is one of

two people killed while riding a bicycle in Wayne County this year,

according to preliminary data from the state police Traffic Crash

Reporting System. There have been a total of 225 crashes involving

vehicles and bikes that resulted in another 167 injuries. The 32-year-old man

from Inkster who struck Zduniak was driving a 2007 Dodge Caliber. The

crash investigation is ongoing as state police investigators await

test results to determine whether the driver was sober at the time of

the collision.

.png)

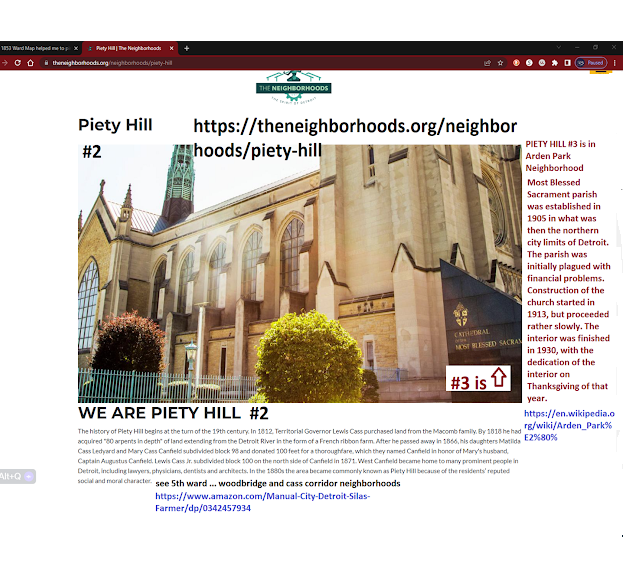

.png)